Our contributing editor Daniela Witten concludes her two-part column about her experience as a journal editor. Part 1 (which you can read here) in the August 2025 issue, contains her thoughts about editors, associate editors (AEs), and reviewers. In this part, Daniela focuses on advice to authors.

Sometimes papers are (desk) rejected: don’t take it personally

At the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (JRSSB), a substantial portion of papers are desk rejected (i.e., rejected without being sent out for review). Occasionally, this is because JRSSB is clearly not a good fit (for instance, a paper that presents a routine data analysis for some scientific problem, but does not propose new statistical methodology). More often, though, desk rejections are a judgment call: perhaps the editor feels that there have been too many recent submissions on this particular topic, or the AE with relevant expertise is totally swamped, or it just subjectively seems that the submission is unlikely to survive the peer review process. The latter is particularly important since there simply are not enough qualified reviewers to review all of the papers that get submitted: the system would break if there were no desk rejections.

Before I became Joint Editor at JRSSB, when one of my papers was (occasionally) desk rejected, I thought that this was an unspeakably terrible outcome that certainly had never happened to even a single one of my colleagues in the history of time. Now I know the truth: desk rejections happen to everyone, for a variety of reasons.

If your paper has been desk rejected, then you should see whether the editor gave you constructive feedback that you can use to improve your submission. If so, then incorporate it into your paper… and then move on to another journal.

(What might constructive feedback look like for a desk rejection? It might not be detailed or technical, since the paper has not been reviewed by experts in the subject area. But if the editor says, for instance, that your paper lacks novelty, or that the contribution is unclear, or that you seem to have missed key references, then that could be a sign that you should edit your paper—exposition and/or content—before submitting it elsewhere.)

And a desk rejection can even be a small mercy. It’s better to receive a desk rejection after two weeks than a (non-desk) rejection nine months later. I speak from experience!

Finally, remember that a rejection (either a desk rejection or a rejection after review) typically does not mean that your paper is technically unsound or fatally flawed. More often than not, it just means that it is not a match for this journal at this time. For instance, at JRSSB, one of the primary publication criteria is methodological novelty, so technically sound papers that are just not that novel (in the very subjective eyes of an editor, AE, and reviewers) are rejected.

Most papers get in “by the skin of their teeth”

At JRSSB, I have never seen a paper that was uniformly beloved by all readers (editor, associate editor, and reviewers) in the first round of review. More often than not, papers go through at least two rounds of review, and only after painstaking revisions by the authors are all readers (the editor, AE, and reviewers) eventually satisfied—or at least, satisfied enough—that the paper can be accepted. (“Satisfied enough” is important here: perfection is both unnecessary and unachievable.)

So, any published paper is imperfect: it almost certainly could have been further improved by another round of review (or six). And actually, a particular paper might be far from perfect: it might have just barely been accepted by the journal.

Furthermore, any published paper may have benefited from an element of luck in the review process (e.g. a reviewer ran out of time to prepare a review, and so signed off on the paper without careful scrutiny). What does this mean for you? Hoping for good luck is not a viable statistical strategy, and therefore, you should expect that in order to publish in a given journal, your paper will have to be better than the majority of papers published in that journal.

But hey… I am certainly rooting for your paper to be a lucky one!

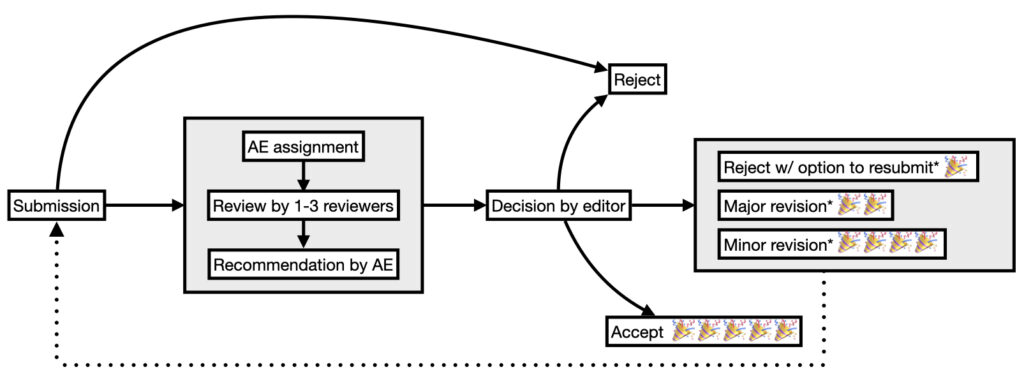

Figure 1. A schematic of a single “round of review” in the field of statistics, reprinted from Daniela’s previous column. Confetti poppers (🎉) indicate editorial decisions for which you should throw a party.

It’s party time

In Figure 1 above, four of the editorial decisions (Accept, Rejection with option to resubmit, Major revision, Minor revision) are marked by confetti poppers (🎉). These are the editorial decisions for which you should throw a party. Your paper was not rejected!!! Hooray!!!!! Please honor this fantastic news. If your paper goes through several rounds of review before eventual publication, then you can have several parties! The number of confetti poppers (e.g., 🎉 vs. 🎉🎉🎉🎉) associated with the editorial decision provides a shorthand for how hard you should celebrate. (It is up to you how to determine the units, i.e., the extent of celebration associated with each confetti popper.)

Some people ask whether it is really appropriate to throw a party for a rejection with the option to resubmit (“R&R”). The answer to this question is an unequivocal YES. Anything that is not a full rejection deserves a party. (Life is short, etc.) Also, in most cases an editor will only invite a resubmission if they see a path forward for the paper in that journal.

After the party is complete, it is time to get to work addressing any comments from the editor, AE, and reviewers (unless your paper was accepted, in which case you should still be celebrating). I suggest that you prioritize the revision above all other tasks: if you can get your paper back to the journal while it is still fresh in everybody’s mind, then the remainder of the review process is more likely to run smoothly. Also, this is not a time to argue: this is a time to do what you were asked to do if it is possible, and if not possible, then to clearly explain the reasons why. By doing what is asked, you make it easy for the editor to accept your paper.

Rejections happen

What if your paper was rejected? You will likely feel sad, and that is okay: it is important to feel your feelings. However, don’t let it wreck you. We all get papers rejected at times. If one of the reviews is factually wrong then you could consider contacting the editor (although this is almost never met with success). Generalized complaints to the editor are equally unlikely to be fruitful. Instead, read the reviews and decision letter, and think about whether you can use them to improve your work. If you can, then do so; and if not, then pick yourself up and try again.

Occasionally people get mad about rejections, and blame the editor or AE or reviewers for not understanding the paper, or not being sufficiently knowledgeable about the topic, etc. To this I say: it is your job, as an author, to write a paper in a way that enables the editor, AE, and reviewer to appreciate your work. Can you re-write your paper so that it fares better next time?

Edit, edit and edit again

And that brings me to my last suggestion for authors: edit your manuscript. Almost never is the first set of words you put on a page the best way to communicate an idea. In fact, for me personally, the 189th set of words is usually also not the best way to communicate the idea.

I could write a whole column about this, but instead I will point you to an editorial in the March 2025 issue of Nature Biotechnology that expresses this beautifully: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02584-1.

Once you have found the most effective way to communicate your ideas, here is a helpful pre-submission checklist by Jacob Bien: https://faculty.marshall.usc.edu/Jacob-Bien/papers/manuscript-checklist.pdf.

I believe that the most highly-cited papers in statistics are not necessarily the most technically challenging or even (dare I say it?!) the most innovative. The most highly-cited papers are the best-written papers, because when a paper is well-written, people understand what it’s about and why it’s useful. Write your paper well, and it will pay off not just in a smoother publication process, but also in future recognition.