Our contributing editor Daniela Witten shares her thoughts on the editorial process, and some advice for associate editors and reviewers, written from the perspective of an editor and a human:

I submitted my first paper to Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (JRSSB) as a grad student. When it was accepted for publication, I called my mother—who is not a statistician and had never heard of the journal—and breathlessly told her, without a hint of irony, that whatever happens in my life, I always will have published in JRSSB.

A few years later, as junior faculty, a paper that I submitted to JRSSB was invited for revision. I immediately reached out to my co-author… only to discover that they had just had a baby and were not available to help (or rather, not available right that minute). I remember thinking to myself—again, no irony—that lots of people can have babies, but very few can publish in JRSSB. (Over time, I have developed a more nuanced understanding of this very important topic, which I discuss in a previous column.)

Time passed, and I chilled out (I think? a little bit? maybe? [TO DO: fact-check with my grad students]). Okay fine, maybe I didn’t chill out. As I was saying, time passed, and in early 2022 I got an email from Steffen Lauritzen, who was near completion of his three-year term as Joint Editor of JRSSB, inviting me to serve as the next Joint Editor for the journal. I had all of the feelings at once, from an initial moment of “I wonder if he sent this to the wrong person?!” to the realization “Wow, I am old!”

As the end of my three-year term approaches, I am devoting two Written by Witten columns to my experience. This first one focuses on what I’ve learned as an editor, and provides advice to those upon whose efforts I relied: namely, the associate editors (AEs) and reviewers. The second one, which will appear in the next issue of the IMS Bulletin, is geared towards authors.

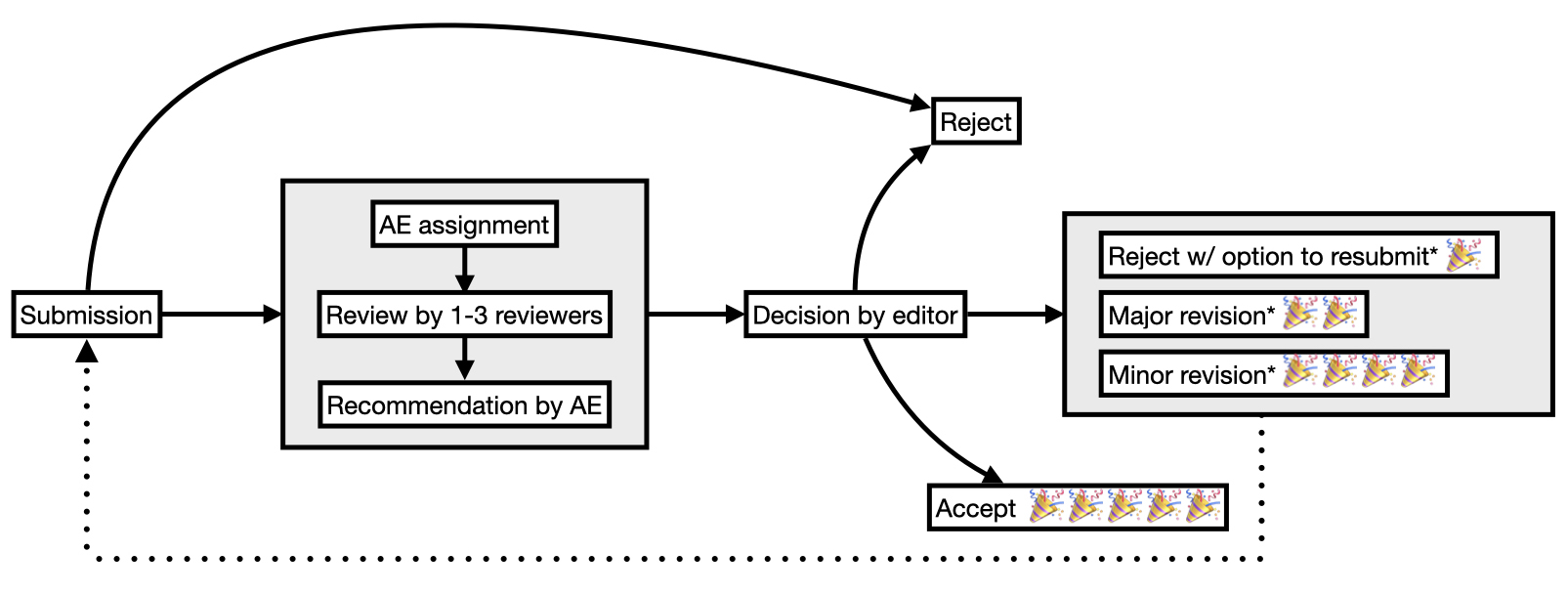

Figure 1, below, and its caption summarize the publication process in statistics.

Figure 1. A schematic of a single “round of review” in the field of statistics. An initial submission might be immediately rejected by the editor: this is called a “desk rejection”. If not, then it is assigned to an associate editor (AE), whose identity is unknown to the author. The AE sends it to between one and three anonymous reviewers, whose reports form the basis for the AE’s recommendation. Then the editor makes a decision. If the paper is accepted then that is the end of the story (but papers are almost never accepted in the “first round”!). And if the paper is rejected, then that is the end of the story at that journal. For all other decisions, the authors have the opportunity to re-submit the paper to the same journal, and the process starts again with another round of review (see dotted line). Unless there is a desk rejection, a round of review typically takes at least three to four months. Confetti poppers indicate editorial decisions for which you should throw a party (units of celebration are at your discretion).

Humans are flawed

When I was a new assistant professor, my then-colleague Peter Hoff told me that as a graduating PhD student he thought he knew 80% of what’s important in the field of statistics; as an associate professor he thought he knew 10%; and as a full professor he realized he knew no more than 5%. I will add to this anecdote that, based on my personal experience, journal editors know far less than 5% of the field, and the amount that they know seems to decrease daily.

Furthermore, at JRSSB, submissions are randomly assigned to one of three Joint Editors. So, even in the unlikely event that one of the three Joint Editors does happen to be an expert in the area of your paper, there’s only a ⅓ chance that they will handle your submission.

The associate editor may know a fair bit about your area, but there are no guarantees. Hopefully the reviewers are experts in the topic of your paper (though there are no promises in love, war, or peer review). And sometimes, even if a reviewer is an expert, their report might make you think that they aren’t! I have received scathing emails from authors of rejected papers telling me that clearly the AE or reviewer was grossly unqualified to assess the paper… and as often as not, this has happened in cases where the AE or reviewer involved is, in fact, unquestionably a leader in the field. (Also, before sending an angry email, remember that literally everyone involved in the review process is an unpaid volunteer: in general, statistics journals do not financially compensate their editors, AEs, or reviewers. So, be kind!)

As a human and as an editor, I sometimes make mistakes (to edit-err is human!). In fact, (i) two reasonable and well-intentioned people might disagree on the “correct” decision for a paper; and (ii) avoiding all mistakes would require an infinitely-long review process, and nobody wants that! Fortunately, life is long, and no single editorial error defines a career.

Advice to associate editors

Firstly, thank you for all you do: you are incredible.

Before you send a paper out for review, assess whether it is likely to survive the review process. Is it well-written? Interesting? Clearly-motivated? If not, then recommend a desk rejection without review. There’s no point in asking reviewers to prepare a report if you already know the outcome, and it’s better for an author to find out about a rejection today rather than in six months.

And if you do decide to send the paper out for peer review? Unless you are willing to serve as a reviewer yourself if needed, then I recommend recruiting three reviewers instead of two. This is because reviewers sometimes do not deliver the reports that they have promised, and sometimes deliver reports that are unusable or uninformative. Finding three reviewers now will save you a huge headache later.*

Finally: not everybody needs to serve as an AE for a journal. Yes, the role carries prestige, but other activities that carry a comparable amount of prestige may be a better fit for your personality.** As an AE, you will face a perpetual to-do list that requires attention on a weekly or even daily basis. (Imagine a supermarket with a conveyor belt of editorial responsibilities: you are the only person tasked with bagging the groceries, and your shift lasts three years.) If this sounds unappealing, then I don’t think the AE role is right for you. Conversely, you may enjoy serving as an AE if you enjoy deeply engaging with the literature outside of your immediate research area, are responsive to email, and tend not to procrastinate.

Advice to reviewers

You are the unsung heroes who do the work that makes the entire system work. Thanks for all you do!

Here’s a joke: “How long does it take to review a paper?” The answer is: “Six months, plus an afternoon”. At the risk of spoiling the humor by over-explaining: in many cases, it takes only an afternoon to review a paper. While I appreciate the service provided by peer reviewers, I also wonder if we could all make a collective effort to submit our referee reports a little faster… say, in four to six weeks, plus an afternoon. Perhaps if you pay it forward by submitting your next review promptly, the universe will reward you by giving you a quick decision on your next paper (though hopefully not too quick: you don’t want a desk rejection!). Absent any cosmic reward, you can sleep well knowing that you are an exemplary citizen of the statistical community.

And, a corollary: please do not accept a referee request unless you plan to submit a high-quality report on the timeline specified by the AE. Referee reports that are shoddy or late gum up the system for everyone involved. I will never hear about it if you decline a referee request, but I will hear about it if you accept a referee request and then still haven’t submitted your report after months of reminders. Please do not cause me a headache.

A tip to save time: if a paper is clearly not suitable for publication, then you do not need to write a five-page review. A concise and timely review that summarizes your key concerns will earn you the everlasting gratitude of the AE. The inverse of this is also true: a very long and detailed (and also timely) review is spectacularly helpful for a paper that may eventually be published in the journal.

Be polite! A review that is rude is not much use to an AE or an editor.

And finally, if you are reviewing for a top journal, then remember that it is not “good enough” for a paper to be correct: it needs to be innovative and interesting! If the paper is not innovative, then you can communicate this via private comments to the AE (which, in most journal submission systems, are an option when submitting your review).

Stay tuned for my next column, which will contain advice for authors!

—

* A natural objection to this piece of advice is that finding three reviewers for each paper will over-burden the pool of available reviewers. However, I believe that it is better to err on the side of desk-rejecting more papers, and finding three reviewers for the papers that are not desk-rejected, in order to ensure a timely and high-quality review process.

** Examples of alternatives to serving as AE that carry a comparable amount of prestige: serve as program chair for a machine learning conference (these tend to have relatively compact timelines); write a research monograph; get involved in professional society leadership; serve as a local organizer for a conference; take a leadership role in a large multi-institution federal grant application; etc.